Invest in Women: Accelerate Progress is this year’s International Women’s Day theme. The theme is timely because women in Kenya are underrepresented in leadership, policy, legislation, and governance. Consequently, they face discrimination in resource allocation and access to opportunities.

On the one hand, Kenya’s policies demonstrate good faith toward achieving gender parity. For instance, Kenya’s National Policy on Gender and Development highlights multiple laws that enhance women’s access to financial assets, including:

- The Matrimonial Property Act, 2013

- Marriage Act, 2014

- The Land Act

- The Land Registration Act

Nonetheless, the progress toward women’s empowerment in Kenya is slow, with one 2020 report highlighting that only 29% of Kenyan women are empowered. While “investing” typically alludes to financial resources, policy formation, adoption, implementation, evaluation, and maintenance are the bedrock on which sustainable investments for progress lie.

Therefore, Kenya’s legal fraternity’s investment in society’s progress entails exercising its influence throughout the policy lifecycle and facilitating collective action toward gender parity. So, as a young Kenyan lawyer, how can you leverage your time, knowledge, and skills to invest in women and accelerate progress through policy?

Well, meet Anna Mutavati, an outstanding and passionate lawyer and gender equality champion who has grown her sphere of influence on gender equality from the legal aid clinics in Zimbabwe to leadership positions in the UN.

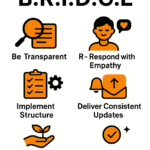

Anna Mutavati is Kenya’s country director of UN Women, an agency established in 2010 to address gender equality and Women’s empowerment in UN member states. Ms.Mutavati unpacks her 25-year career as a lawyer championing gender equality to empower humanity by bridging the gap between policy drafting and implementation, especially among disadvantaged communities. She also reflects on her work at UN Women and the agency’s mandate to identify policy gaps that present bottlenecks for women’s progress and seek viable solutions.

Roots of Resilience: Rising Above A Turbulent Childhood To Empower The Powerless

Ms. Mutavati knew from her formative years that she wanted to be in the justice space. “I wanted laws useful to people, offering help and protection, especially to vulnerable groups that perhaps had limited or no knowledge of their rights. So, I wanted to play my part to be the bridge between the law and the people.”

Ms. Mutavati knew from her formative years that she wanted to be in the justice space. “I wanted laws useful to people, offering help and protection, especially to vulnerable groups that perhaps had limited or no knowledge of their rights. So, I wanted to play my part to be the bridge between the law and the people.”

Her strong sense of justice and advocacy for the oppressed stems from her childhood experiences. Anna grew up in a home marred by domestic violence, and it irked her to watch her father, who was the perpetrator, unleash violence on her mother time and again with zero consequence.

Despite her tender age, the power imbalance and impunity that fueled these acts of violence were apparent. “ Even as a little girl, I knew that was wrong, and the sense of injustice sat it me.” Hence, her inclination for justice led her to the University of Zimbabwe, where she undertook an undergraduate law degree and later a Masters in Women’s Law.

Marrying Her Two Passions, The Law and Advocacy, While Working At The UN

So, how did Ms. Mutavati end up at the helm of UNWomen, and is her law degree relevant to the job?

Instead of applying for a corporate law job in the top-tier firms in her country, she approached the Zimbabwe Women Lawyers Association (ZLWA), an NGO committed to realizing a world free of injustice and inequality. Although ZLWA had no vacancies, she convinced them to let her volunteer for three months while learning from more experienced lawyers. Thanks to her passion for tackling barriers to accessing justice for indigent communities, ZLWA absorbed her into its team.

When asked why she chose to tread off the beaten path, Anna says, “You must invest time at the grassroots or community level; roll up your sleeves and be part of the “dirty” work.”

Ms. Mutavati spent time in legal aid clinics serving clients with limited access to legal services, most of whom were women. She spent countless hours pushing family law cases (inheritance disputes, divorce and division of marital properties, domestic violence), sexual harassment cases, and unfair dismissal cases through the justice system.

Women comprised the majority of clients to the legal aid clinics ZLWA offered. While working there, Anna established that the women they served faced three significant barriers to accessing justice. First, most did not understand the law, while those who understood their fundamental rights did not know the procedure to follow when their rights were violated. Additionally, the women lacked the financial resources to pay for legal services.

Although Anna Mutavati’s experiences date back two decades, the reality is that many Kenyan women today still grapple with these barriers to justice. A closer look at the barriers reveals that they stem from limited access to opportunities like education and access to financial resources.

Bearing this in mind, Ms. Mutavati and the team at ZLWA took several steps to improve access to legal services for the underserved communities where they operated legal clinics.

First, they identified knowledge gaps and curated legal literacy programs focusing on topics the communities held dear. For instance, inheritance law was among the prominent subjects, given that most cases handled featured women who could not prove their contribution to acquiring marital properties.

Besides the women, they also involved the community’s traditional leaders, who were predominantly men. One report by the Kenya Institute for Public Policy and Research Analysis (KIPPRA) highlights how those who implement policies exercise their discretion, which depends largely upon their individual dispositions towards the policies.

Community leaders often step in when the formal legal system fails to trickle down to the grassroots level. “That was an opportunity for us to influence that traditional justice system at the community level, where most women were taking their cases.”

Second, Anna lobbied the MPs in her native Zimbabwe to pass a law on domestic violence; the existing laws prosecuted domestic violence cases under common assault. “We made a big case for that because the male perpetrator in domestic violence has a duty of care to the woman they’re bashing, so this is bigger than the common assault you see on the streets.”

Ms.Mutavati was privileged to be part of the team drafting the new domestic violence law. According to her, her work in the legal aid clinics was instrumental in her contribution to the new law because the lived experiences of all the women who walked through the legal aid clinics inspired her drafting.

Third, while Zimbabwe’s parliament passed the new law on domestic violence, it wasn’t being implemented to the tune that they intended to bring out the severity of the penalty they pushed for. Therefore, she lobbied for and participated in the law’s amendment.

According to Ms. Mutavati, the experience she gained while working at the grassroots level was invaluable for her career. “ When I moved to the UN, I had everything they were looking for, i.e., someone with grounded experience who would bring to the policy table all the knowledge, experience, and connection to what happens between policy and practice.”

Investing in Women To Accelerate Progress Through Policies, Programs, and Initiatives That Empower Women In All Areas of Life

Anna Mutavati considers her job at UN Women a privilege. So, what is the UN Women’s mandate? Also, Given that the UN chose this year’s theme, what is UN Women doing to invest in Kenyan women and accelerate progress?

UN Women, or the United Nations Agency/Entity for Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women, came to be in 2010. Gender equality champions, including Ms. Mutavati, lobbied the UN General Assembly to create an agency that catered exclusively to women’s rights. “We were experiencing and continue to experience discrimination against women in almost every sector.”

According to Ms. Mutavati, various data sources show that women are lagging in every sector due to limited access to opportunities, discriminatory practices, and society’s failure to acknowledge their contributions, just to name a few factors. Therefore, UN Women collaborates with the national government and civil society organizations to retrieve data that demonstrates where the most pressing gender gaps are in the Kenyan context.

The first gap is in governance, and Ms. Mutavati cites Kenya’s political arena as an example. “Governance is about electing leaders to promote policies and leadership through established governance systems. Nonetheless, take a body like parliament where women only comprise 23% of parliamentarians, despite the one-third gender rule.”

According to Ms. Mutavati, such gross underrepresentation means the policies formed do not take on women’s experiences. So, the first core pillar in UN Women’s functionality is ensuring that governance processes are inclusive of women. Besides fair representation, the decisions from governance processes must reflect women’s experiences and aspirations or what they’d expect from their government.

The second UN Women’s pillar is women’s economic empowerment: “While we are pursuing poverty eradication programs, let’s remember that poverty has a female face, necessitating direct and deliberate interventions that address poverty from women’s perspective.” UN Women works with the national government and other stakeholders to establish what keeps Kenyan women poor.

“While temporary interventions are crucial in curbing poverty in the short term, we need to go back to where it all started. Maybe it’s in education, in all the discriminatory practices that are keeping girls out of school or restricting them to less lucrative careers” While UN Women explores all poverty eradication avenues, including short-term measures like investing in women through affirmative action funds, its goal is establishing and tackling the root causes that keep women impoverished.

The third is ending domestic violence against women. “ The UN declared violence against women as the most pervasive form of human rights violation, yet we as a society accept it.” Moreover, a research study by the IMF established that higher levels of violence against women and girls translate to lower levels of economic activity, driven by a significant drop in female employment.

Although there are laws against gender violence in the Kenyan constitution, the gap between policy and practice means perpetrators often walk. Additionally, victims endure public shaming, especially on social media. Moreover, one report established that most Kenyans see domestic violence as a private rather than a criminal matter.

“To think that there is ever justification to take away a life or to maim somebody is worrying. So, how do we reset as a society and discard those norms that make it okay to tolerate violence and make justifications and excuses around it?”

Although UN Women’s long-term strategy in tackling violence against women is challenging the norms that fuel this violence, the organization also prioritizes action supporting gender-based violence victims today. “Should violence occur, where are the systems to respond?” Therefore, the agency’s interim strategy focuses on justice, i.e., removing all barriers to access to justice for Women.

“So, while working with the judiciary, we need to make the justice system re-examine its effectiveness in delivering justice.”

Additionally, UN Women collaborates with counties to ensure that each county has a shelter where victims of violence can take refuge, preventing unnecessary loss of life. Lastly, the agency collaborates with UNFPA, a UN agency focused on healthcare systems, to ensure that health workers handle violence survivors with dignity and empathy when they seek treatment at healthcare facilities.

Fourth, the UN Women’s final mandate in Kenya centers on peace and security for women. “If there is no peace or security, you can forget about any form of societal development.” Ms. Mutavati highlights that women are the most vulnerable populations during conflicts and crises, yet they are excluded from the decision-making processes that generate these crises. “Women have a role to play in peacekeeping and conflict prevention, not just as victims but as active leaders in governance spaces.”

So, which programs does the UN Women Kenyan Chapter offer to rope in the legal fraternity, empowering them to invest in women and accelerate progress?

UN Women currently runs programs in collaboration with the judiciary, training the police, prosecutors, lawyers, and other judiciary members on gender-responsive justice delivery. “Participating in such programs grounds you and creates an awareness of gender issues not taught in law school.”

Nonetheless, besides taking these programs, Kenyan lawyers can help propel UN Women’s gender equality agenda by plugging into law reform processes. “ You can borrow your daily experiences and shed the spotlight on gaps that you experience while adjudicating or preceding over cases. Let’s give that to our members of parliament and let them close the gaps for us.”

Lastly, the experienced lawyers in Kenya’s legal space can aid UN Women’s efforts by mentoring the upcoming generation of lawyers. Mentorship enlightens them about the gender issues veteran lawyers experience and makes them part of the solution. “ I think it’s long overdue that we introduce mandatory gender and law courses to those pursuing law degrees in universities right from the first year of study. By the time we are churning out lawyers, they already view things as we see them and are driven to make a change so that the law starts to work for people.”

Anna Mutavati is a product of mentorship, and one of her mentors as a young lawyer at ZWLA was Ms.Lydia Zigomo, UNFPA’s Regional President For Eastern and Southern Africa. Once you are equipped to do that gender analysis of any situation, you find yourself looking at the law from a gender perspective, identifying gaps, and becoming an activist in your own space, regardless of the niche. If it’s not me to address this gap, how do I bring it to the attention of relevant bodies?”

Anna Mutavati’s Nuggets of Wisdom for Young Lawyers

- Never stop learning because life never stops teaching. There’s something new to learn every day in the field of law, so consider expanding into contemporary areas of practice like climate change and energy, which are begging for young and vibrant lawyers.

- Roll up your sleeves and do the “dirty” work. “ You cannot create substance simply by reading it; you must be there to experience it. There’s no shortcut to starting where it really matters. When you rise, people will see the substance that drives the person behind you.

- Never forget that the law is a tool to help people, including women. “Humanizing each case that goes through the justice system helps our impact as lawyers in helping people get the protections intended by the law, the constitution, and international human rights instruments.”

The law’s primary purpose is advancing humanity, with the business aspect being secondary. “Behind this whole conversation around humanity, most women have it twice or thrice as difficult to access justice.

When we work together as members of the legal fraternity, we can expand the efforts to overcome barriers to justice for women and be the bridge between the law and the people. “Otherwise, we have laws that are passed, and nobody remembers them; they just gather dust on the shelves while violations of human rights occur daily with impunity.”

Essentially, gender equality is an issue of our time, so take advantage of UN Women’s programs to grow your knowledge of gender policies and become the change you hope to see.

Resources:

https://psyg.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NATIONAL-POLICY-ON-GENDER-AND-DEVELOPMENT.pdf

https://www.treasury.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Women-Empowerment-Report-2020.pdf

https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/AD560-Most-Kenyans-see-domestic-violence-as-private-not-criminal-matter-Afrobarometer-4oct22.pdf