March 10th is the International Day of Women Judges (IDWJ), a day set aside by the UN to recognize the contributions of women judges worldwide. According to the United Nations Development Fund, Women’s meaningful representation in justice is a precondition to bringing justice to those most need it.

Kenya’s judiciary is among the institutions leaning toward gender parity, with an almost equal number of male and female appointees. Nonetheless, how has the increase in women judges and magistrates influenced Kenya’s judiciary?

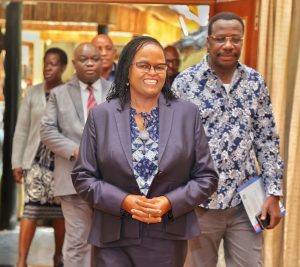

As we reflect on their contributions, we derive insights from the insights of Hon. Lady Justice Patricia Nyaundi, a high court judge, and Hon. Caroline Kendagor.

Lady Justice Nyaundi expressed her reflections during an interview on Spice FM’s Situation Room on 8th March 2024, while Caroline Kendagor spoke to us on the Winning at Law podcast.

What Does it Take For Women Lawyers to Occupy A Seat at the Bench?

Lady Justice Nyaundi attributes the entry of women into the bar as magistrates and top judges to the trailblazers, including Justices Effie Awuor and Joyce Aluoch. She applauds them for disrupting wrongful societal framing/ imagination that because women have less physical strength than men, they are intellectually inferior.

“When you take the time to reflect what these women of firsts did in the judiciary, you see that, really, justice is not genderized.” According to Justice Nyaundi, when women enter the bench, they show up with the benefits of their real-life experiences. “When we allow women into spaces, they come with their world views, and sometimes it takes someone of the same gender to appreciate the context we’re dealing with.”

She highlights that the presence of women judges and magistrates on the bench is not tokenism but a right. “We need to communicate to the public that we are not in these positions by virtue of our biology but because the country owes us.” She refers to the pioneering judges and highlights that their contributions to the judiciary debunk the belief that women only succeed when they start at lower ranks and grow into bigger roles.

Empathy and Action: Women and Girls In Carceral Setting

This year’s IDWJ’s theme is Empathy and Action: Women and Girls in Carceral Setting. Historically, women seeking justice from Kenyan courts often end up with the short end of the stick. So, is there a mindset shift that women judges and magistrates tap into when handling cases for civilian women processed in the justice system?

According to Justice Nyaundi, running courts with the consciousness and empathy for the responsibilities of the civilians within the justice system helps mitigate potential risks to children’s welfare. For example, starting court sessions early and finishing the mentions releases mothers to return to their children.

Second, exercising discretion, especially when handling petty crimes and setting bond and bail terms, also matters. Justice Nyaundi highlights scenarios whereby women incarcerated for petty crimes take up space in jail facilities, sometimes with their children, yet in retrospect, it’s unnecessary. “Are you setting bails and bonds that make it impossible for women in petty crimes to pay? Do they need to take up space in incarceration centers?”

Third, affording the prosecution unnecessary adjournments and prolonging the matter is also a barrier to justice for individuals, especially women and girls, in carceral settings. Also, ensuring the availability of in-camera hearings that preserve the dignity of the victims giving their testimonies demonstrates empathy in action during the administration of justice.

Does the Female Representation at the Courts Percolate to Kenyan Women Seeking Justice?

Besides the primary measures taken at the court level, Justice Nyaundi applauds the establishment of alternative conflict resolution avenues. She celebrates the work of judiciary officers like Caroline Kendagor in dispelling the “drama” and getting to the root of the conflict.

Caroline Kendagor is the Deputy registrar for Court-annexed Mediation and highlights that her department has registered a high success rate in child custody and maintenance cases filed in court. “Women file most of these cases.” Her department has also successfully mediated cases around the matrimonial division of property. “Generally, we’re allowing them to shift the conversation around the balance of power because of the threats that come with litigation, especially when you can’t afford to get an advocate to pursue your case. Also, there are times when plaintiffs struggle to articulate themselves in court but can do so in mediation.”

Therefore, the ripple effect of court-annexed mediation is that it empowers other women to approach the courts. Justice Nyaundi concludes by saying that at the end of the day, Kenyan women judges are conscious of the fact that they speak the “bread and butter” issues. Additionally, her experiences as a human being of what bedevils society must reflect in the decisions/ interpretations of the law- they must address the inequalities and challenges the society faces. “When sitting at the bench, I sit as a wife, mother, daughter, sister, and an employer.”

Challenges Facing Women Judges in Kenya’s Judiciary

One question that lingers is, given that the judiciary appointments in Kenya adhere to the two-thirds gender rule, why do we continue making gender equality a present conversation, even when women’s rights have been recognized in the judicial sector?

Justice Nyaundi acknowledges and celebrates the fact that women judges today do not face most of the hurdles the pioneers like Justice Effie Awuor faced. Even so, she views the calls to shift focus away from the gender equality conversation as a deliberate denial of what the facts are on the ground.

Lady Justice Nyaundi highlights that while the judiciary has succeeded in getting the numbers, the next step is working toward translating those numbers into actual benefits for justice consumers. “Moreover, it still tickles me that if I fail to announce my first name, everyone assumes I am a man.” Caroline Kendagor also highlights instances when she has experienced pushback from litigants who feel she has no right to decide on their cases primarily due to her gender.

Finally, Lady Justice Nyaundi expresses that IDWJ is not for women judges and magistrates alone. She acknowledges that the observance also celebrates the men who have bitten the bullet to ensure justice is accessible to all, including women. “You can be a woman by nature or nurture, and so there’s a generation of men in the judiciary who fully appreciate that we cannot show up to public spaces with these stereotypes.”

Shaping the Next Generation of Female Judges

Justice Nyaundi began by acknowledging that the continuous thread in her career is the presence of a big sister who has inspired and challenged her. Therefore, as she reflects on this year’s IDWJ, she acknowledges the need to hold the door for those coming after her. Caroline Kendagor is also a product of mentorships and peer reviews that have nurtured her career.

Consequently, Lady Justice Nyaundi and Caroline Kendagor mentor younger lawyers in various dockets. Hon. Caroline’s take is candid conversations with her mentees about progressing in their legal careers, encouraging them to seize opportunities that arise.

On the same wavelength, Lady Justice Nyaundi advises the next generation of women judges: “When people look at you, they should see merit. People may open doors for you, but you must deliver because you respect them.”

Parting Shot

Hon. Lady Justice Nyaundi and Hon. Caroline Kendagor express that they feel privileged to be part of a system that makes the law work. Therefore, we join them in celebrating the pioneer women judges and the men who are determined that when we say justice for all, all means all and not only those we choose to see.

NB: This feature is an abridged version of the interview hosted on Spice FM by Eric Latiff, CT Muga, and Ndu Okoh, with Hon. Lady Justice Patricia Nyaundi as the guest interviewee. It also features excerpts from the Winning at Law podcast episode #4, where Hon. Caroline Kendagor talks to Dissi Obanda about her career as a court officer.